- Published on

Vue Testing Crash Course

- Authors

- Name

- Gábor Soós

- @sonicoder86

You have nearly finished your project, and only one feature is left. You implement the last one, but bugs appear in different parts of the system. You fix them, but another one pops up. You start playing a whack-a-mole game, and after multiple turns, you feel messed up. But there is a solution, a life-saver that can make the project shine again: write tests for the future and already existing features. This guarantees that working features stay bug-free.

In this tutorial, I'll show you how to write unit, integration and end-to-end tests for Vue applications.

1. Types

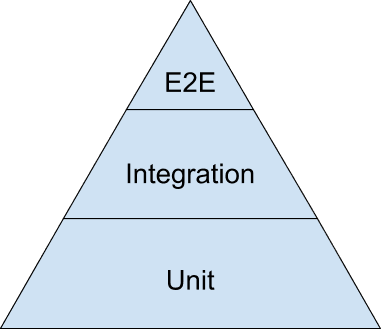

Tests have three types: unit, integration and end-to-end. These test types are often visualized as a pyramid.

The pyramid indicates that tests on the lower levels are cheaper to write, faster to run and easier to maintain. Why don't we write only unit tests then? Because tests on the upper end give us more confidence about the system and they check if the components play well together.

To summarize the difference between the types of tests: unit tests only work with a single unit (class, function) of code in isolation, integration tests check if multiple units work together as expected (component hierarchy, component + store), while end-to-end tests observe the application from the outside world (browser).

2. Test runner

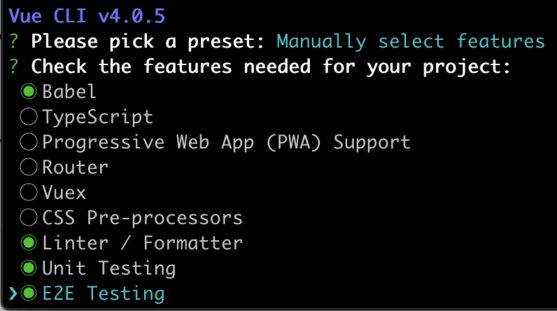

For new projects, the easiest way to add testing to your project is through the Vue CLI. When generating the project (vue create myapp), you have to manually select Unit Testing and E2E Testing.

When the installation is finished, multiple additional dependencies will appear in your package.json file:

@vue/cli-plugin-unit-mocha: plugin for unit/integration tests with Mocha@vue/test-utils: helper library for unit/integration testingchai: assertion library Chai

From now on, unit/integration tests can be written in the tests/unit directory with *.spec.js suffix. The directory of the tests is not hardwired; you can modify it with a command-line argument:

vue-cli-service test:unit --recursive 'src/**/*.spec.js'

The recursive parameter tells the test runner to search for the test files based on the following glob pattern.

3. Single unit

So far, so good, but we haven't written any tests yet. Let's write our first unit test!

describe('toUpperCase', () => {

it('should convert string to upper case', () => {

// Arrange

const toUpperCase = (info) => info.toUpperCase()

// Act

const result = toUpperCase('Click to modify')

// Assert

expect(result).to.eql('CLICK TO MODIFY')

})

})

This verifies if the toUpperCase function converts the given string to upper case.

The first thing to do (arrange) is to get the target (here a function) into a testable state. It can mean importing the function, instantiating an object, and setting its parameters. The second thing is to execute that function/method (act). Finally, after the function has returned the result, we make assertions for the outcome.

Mocha gives us two functions describe and it. With the describe function we can organize our test cases around units: a unit can be a class, a function, component, etc. Mocha doesn't have a built-in assertion library, that's why we have to use Chai: it can set expectations on the outcome. Chai has many different built-in assertions. These assertions, however, do not cover all use-cases. Those missing assertions can be imported with Chai's plugin system, adding new types of assertions to the library.

Most of the time, you will be writing unit tests for the business logic that resides outside of the component hierarchy, for example, state management or backend API handling.

4. Component display

The next step is to write an integration test for a component. Why is it an integration test? Because we no longer test only the Javascript code, but rather the interaction between the DOM as well as the corresponding component logic.

// src/components/Footer.vue

<template>

<p class="info">{{ info }}</p>

<button @click="modify">Modify</button>

</template>

<script>

export default {

data: () => ({ info: 'Click to modify' }),

methods: {

modify() {

this.info = 'Modified by click'

},

},

}

</script>

The first component we test is one that displays its state and modifies the state if we click the button.

// test/unit/components/Footer.spec.js

import { expect } from 'chai'

import { shallowMount } from '@vue/test-utils'

import Footer from '@/components/Footer.vue'

describe('Footer', () => {

it('should render component', () => {

const wrapper = shallowMount(Footer)

const text = wrapper.find('.info').text()

const html = wrapper.find('.info').html()

const classes = wrapper.find('.info').classes()

const element = wrapper.find('.info').element

expect(text).to.eql('Click to modify')

expect(html).to.eql('<p class="info">Click to modify</p>')

expect(classes).to.eql(['info'])

expect(element).to.be.an.instanceOf(HTMLParagraphElement)

})

})

To render a component in a test, we have to use shallowMount or mount from Vue Test Utils. Both methods render the component, but shallowMount doesn't render its child components (child elements will be empty elements). When including the component under test, we can reference it relatively ../../../src/components/Footer.vue or use the provided alias @. The @ sign at the start of the path references the source folder src.

We can search in the rendered DOM with the find selector and retrieve its HTML, text, classes or native DOM element. If we are searching for a non-existing fragment, the exists method can tell if it exists. It is enough to write one of the assertions; they stand there only to show the different possibilities.

5. Component interactions

We have tested what can we see in the DOM, but we haven't made any interactions with the component. We can interact with a component through the component instance or the DOM.

it('should modify the text after calling modify', () => {

const wrapper = shallowMount(Footer)

wrapper.vm.modify()

expect(wrapper.vm.info).to.eql('Modified by click')

})

The above example shows how to do it with the component instance. We can access the component instance with the vm property. Functions under methods and properties on the data object (state) are available on the instance. In this case, we don't touch the DOM.

The other way is to interact with the component through the DOM. We can trigger a click event on the button and observe the displayed text.

it('should modify the text after clicking the button', () => {

const wrapper = shallowMount(Footer)

wrapper.find('button').trigger('click')

const text = wrapper.find('.info').text()

expect(text).to.eql('Modified by click')

})

We trigger the click event on the button, and it results in the same outcome as we have called the modify method on the instance.

6. Parent-child interactions

We have examined a component separately, but a real-world application consists of multiple parts. Parent components talk to their children through props, and children talk to their parents through emitted events.

Let's modify the component that it receives the display text through props and notifies the parent component about the modification through an emitted event.

export default {

props: ['info'],

methods: {

modify() {

this.$emit('modify', 'Modified by click')

},

},

}

In the test, we have to provide the props as input and listen to the emitted events.

it('should handle interactions', () => {

const wrapper = shallowMount(Footer, {

propsData: { info: 'Click to modify' },

})

wrapper.vm.modify()

expect(wrapper.vm.info).to.eql('Click to modify')

expect(wrapper.emitted().modify).to.eql([['Modified by click']])

})

The method shallowMount and mount has a second optional parameter, where we can set the input props with propsData. The emitted events become available from the emitted methods result. The name of the event will be the object key, and each event will be an entry in the array.

7. Store integration

In the previous examples, the state was always inside the component. In complex applications, we need to access and mutate the same state in different locations. Vuex, the state management library for Vue, can help you organize state management in one place and ensure it mutates predictably.

const store = {

state: {

info: 'Click to modify',

},

actions: {

onModify: ({ commit }, info) => commit('modify', { info }),

},

mutations: {

modify: (state, { info }) => (state.info = info),

},

}

const vuexStore = new Vuex.Store(store)

The store has a single state property, which is the same what we have seen on the component. We can modify the state with the onModify action that passes the input parameter to the modify mutation and mutates the state.

We can start by writing unit tests separately for each function in the store.

it('should modify state', () => {

const state = {}

store.mutations.modify(state, { info: 'Modified by click' })

expect(state.info).to.eql('Modified by click')

})

Or we can construct the store and write an integration test. This way, we can check if the methods play together instead of throwing errors.

import Vuex from 'vuex'

import { createLocalVue } from '@vue/test-utils'

it('should modify state', () => {

const localVue = createLocalVue()

localVue.use(Vuex)

const vuexStore = new Vuex.Store(store)

vuexStore.dispatch('onModify', 'Modified by click')

expect(vuexStore.state.info).to.eql('Modified by click')

})

First, we have to create a local instance of Vue. Why is it needed? The use statement is necessary on the Vue instance for the store. If we don't call the use method, it will throw an error. By creating a local copy of Vue, we also avoid polluting the global object.

We can alter the store through the dispatch method. The first parameter tells which action to call; the second parameter is passed to the action as a parameter. We can always check the current state through the state property.

When using the store with a component, we have to pass the local Vue instance and the store instance to the mount function.

const wrapper = shallowMount(Footer, { localVue, store: vuexStore })

8. Routing

The setup for testing routing is a bit similar to testing the store. You have to create a local copy of the Vue instance, an instance of the router, use the router as a plugin and then create the component.

<div class="route">{{ $router.path }}</div>

The above line in the component's template will display the current route. In the test, we can assert the content of this element.

import VueRouter from 'vue-router'

import { createLocalVue } from '@vue/test-utils'

it('should display route', () => {

const localVue = createLocalVue()

localVue.use(VueRouter)

const router = new VueRouter({

routes: [{ path: '*', component: Footer }],

})

const wrapper = shallowMount(Footer, { localVue, router })

router.push('/modify')

const text = wrapper.find('.route').text()

expect(text).to.eql('/modify')

})

We have added our component as a catch-them-all route with the * path. When we have the router instance, we have to programmatically navigate the application with the router's push method.

Creating all the routes can be a time-consuming task. We can speed up the orchestration with a fake router implementation and pass it as a mock.

it('should display route', () => {

const wrapper = shallowMount(Footer, {

mocks: {

$router: {

path: '/modify',

},

},

})

const text = wrapper.find('.route').text()

expect(text).to.eql('/modify')

})

We can use this mocking technique also for the store by declaring the $store property on mocks.

it('should display route', () => {

const wrapper = shallowMount(Footer, {

mocks: {

$router: {

path: '/modify',

},

$store: {

dispatch: sinon.stub(),

commit: sinon.stub(),

state: {},

},

},

})

const text = wrapper.find('.route').text()

expect(text).to.eql('/modify')

})

9. HTTP requests

Initial state mutation often comes after an HTTP request. While it is tempting to let that request reach its destination in a test, it would also make the test brittle and dependant on the outside world. To avoid this, we can change the request’s implementation at runtime, which is called mocking. We will use the Sinon mocking framework for it.

const store = {

actions: {

async onModify({ commit }, info) {

const response = await axios.post('https://example.com/api', { info })

commit('modify', { info: response.body })

},

},

}

We have modified the store implementation: the input parameter is first sent through a POST request, and then the result is passed to the mutation. The code becomes asynchronous and gets an external dependency. The external dependency will be the one we have to change (mock) before running the test.

import chai from 'chai'

import sinon from 'sinon'

import sinonChai from 'sinon-chai'

chai.use(sinonChai)

it('should set info coming from endpoint', async () => {

const commit = sinon.stub()

sinon.stub(axios, 'post').resolves({

body: 'Modified by post',

})

await store.actions.onModify({ commit }, 'Modified by click')

expect(commit).to.have.been.calledWith('modify', { info: 'Modified by post' })

})

We are creating a fake implementation for the commit method and change the original implementation of axios.post. These fake implementations capture the arguments passed to them and can respond with whatever we tell them to return. The commit method returns with an empty value because we haven't specified one. axios.post will return with a Promise that resolves to an object with the body property.

We have to add Sinon as a plugin to Chai to be able to make assertions for the call signatures. The plugin extends Chai with the to.have.been.called property and to.have.been.calledWith method.

The test function becomes asynchronous: Mocha can detect and wait for the asynchronous function to complete if we return a Promise. Inside the function, we wait for the onModify method to complete and then make an assertion wether the fake commit method was called with the parameter returned from the post call.

10. The browser

From a code perspective, we have touched every aspect of the application. There is a question we still can’t answer: can the application run in the browser? End-to-end tests written with Cypress can answer the question.

The Vue CLI takes care of the orchestration: starts the application and runs the Cypress tests in the browser, and then shuts down the application. If you want to run the Cypress tests in headless mode, you have to add the --headless flag to the command.

describe('New todo', () => {

it('it should change info', () => {

cy.visit('/')

cy.contains('.info', 'Click to modify')

cy.get('button').click()

cy.contains('.info', 'Modified by click')

})

})

The organization of the tests is the same as with unit tests: describe stands for grouping, it stands for running the tests. We have a global variable, cy, which represents the Cypress runner. We can command the runner synchronously about what to do in the browser.

After visiting the main page (visit), we can access the displayed HTML through CSS selectors. We can assert the contents of an element with contains. Interactions work the same way: first, select the element (get) and then make the interaction (click). At the end of the test, we check if the content has changed or not.

Summary

We have reached the end of testing use-cases. I hope you enjoyed the examples and they clarified many things around testing. I wanted to lower the barrier of starting to write tests for a Vue application. We have gone from a basic unit test for a function to an end-to-end test running in a real browser.